Le storie, le interviste, i personaggi del nuovo numero di Rivista Studio.

Il discorso di Faulkner che conquistò la platea dei Nobel

Accanto alla kermesse dei premi Nobel, negli anni si è sviluppato un sottogenere che gli appassionati e gli addetti ai lavori non considerano meno importante e simbolico della cerimonia stessa: quello degli acceptance speech, i discorsi che i freschi vincitori del Nobel consegnano alla Storia.

Nell’ottobre del 1954 Ernest Hemingway, dopo essersi visto consegnare il Nobel per la letteratura, fece un celebre discorso in cui disse «scrivere, nella sua forma migliore, è una vita solitaria» e lodò il valore insito nel lavorare in solitudine. Alice Munro, la canadese ultima vincitrice del titolo, l’anno scorso rivoluzionò la pratica facendosi intervistare dall’Accademia di Svezia. Ma uno dei discorsi più ispirati e riusciti fu quello del 1949 dello scrittore William Faulkner, premiato col Nobel per la letteratura per il suo L’urlo e il furore (1929).

Il suo discorso, ascoltabile in fondo a questo articolo, esordì così:

Ladies and gentlemen,

I feel that this award was not made to me as a man, but to my work – a life’s work in the agony and sweat of the human spirit, not for glory and least of all for profit, but to create out of the materials of the human spirit something which did not exist before. So this award is only mine in trust. It will not be difficult to find a dedication for the money part of it commensurate with the purpose and significance of its origin. But I would like to do the same with the acclaim too, by using this moment as a pinnacle from which I might be listened to by the young men and women already dedicated to the same anguish and travail, among whom is already that one who will some day stand here where I am standing.

Si trattò essenzialmente di uno speech incentrato sul valore non soltanto della scrittura, ma dell’umanità in quanto tale, che Faulkner – nell’era dei conflitti mondiali e della bomba atomica – si rifiuta di considerare condannata; crede invece che il ruolo del poeta e dello scrittore sia esattamente quello di perpetuarla «innalzando i cuori» degli uomini dai travagli della loro vita quotidiana.

I decline to accept the end of man. It is easy enough to say that man is immortal simply because he will endure: that when the last dingdong of doom has clanged and faded from the last worthless rock hanging tideless in the last red and dying evening, that even then there will still be one more sound: that of his puny inexhaustible voice, still talking.

I refuse to accept this. I believe that man will not merely endure: he will prevail. He is immortal, not because he alone among creatures has an inexhaustible voice, but because he has a soul, a spirit capable of compassion and sacrifice and endurance. The poet’s, the writer’s, duty is to write about these things. It is his privilege to help man endure by lifting his heart, by reminding him of the courage and honor and hope and pride and compassion and pity and sacrifice which have been the glory of his past. The poet’s voice need not merely be the record of man, it can be one of the props, the pillars to help him endure and prevail.

(via)

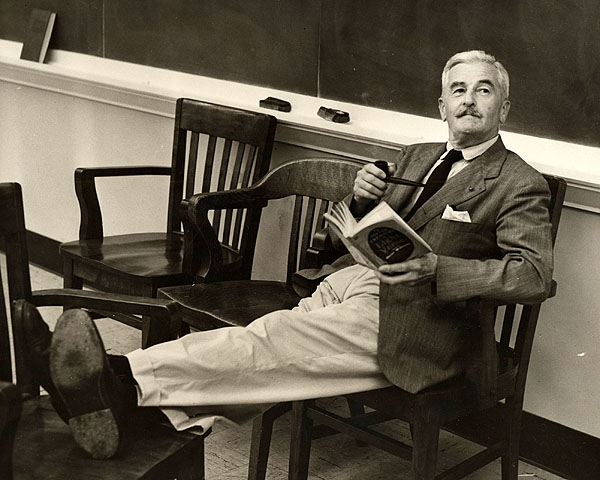

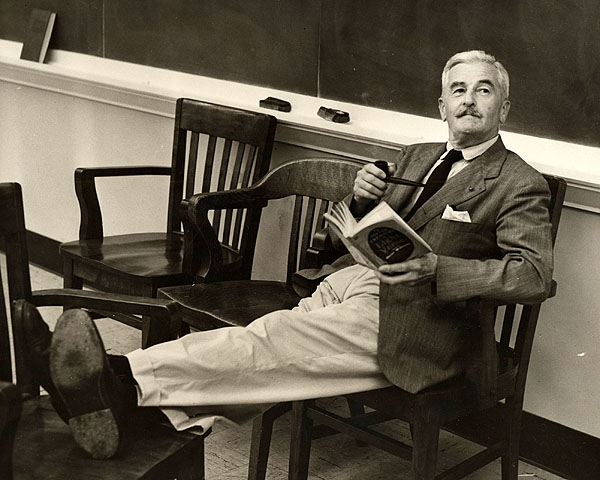

Nella foto: William Faulkner (1897-1962).

Come funziona Jigsaw, la divisione (poco conosciuta) di Google che sta cercando di mettere la potenza di calcolo digitale del motore di ricerca al servizio della democrazia, contro disinformazione, manipolazioni elettorali, radicalizzazioni e abusi.

Reportage dalla "capitale del sud" dell'Ucraina, città in cui la guerra ha imposto un dibattito difficile e conflittuale sul passato del Paese, tra il desiderio di liberarsi dai segni dell'imperialismo russo e la paura di abbandonare così una parte della propria storia.